Resisting the warrior in me

I was asked not too long ago if I considered myself a ‘warrior.’ I immediately said no. The notion that I would need another noun or adjective that emphasized strength and fighting felt like another reminder that I was both Black and femme in a society that tends to heighten our resilience, abuse it, and also weaponize the strength we’ve had to develop to excuse a world from loving us fully. Sure, I consider myself grounded and rooted—and there’s strength in that. My recent years, however, have aligned with those of so many Black femme leaders, especially those of us who are darker in hue, who have pushed back against the normalization of us suppressing the full range of emotions we have and everyone expecting us to be every where, all the time, perfect, doing all the things, while also being undermined and dismissed in our doings. Indeed, my work on the ground (while also teaching and working) post the murders of Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Jr. and Sandra Bland, caused me to personally declare “I need a Radical Sabbatical.” Which led me to inquire more about rest and reinvention: who can afford it, have it and when? That that inquiry has opened up an opportunity to explore that question via a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. But it is not lost on me that this, still requires work.

I am a fighter, by default, thanks to a world designed to make that a constant. The data is never enough; for society to move, it requires those already socially handicapped to pick up whatever they have and march, protest, demand. But as a girl I never wanted to be all that. (For those who know me personally, you have seen this photo many times. I have way more baby pictures, but this remains one of my faves.)

At threeish, I was more obsessed with getting my hair braided and nails painted a bright color like my mom. I had deep dimples then, evidence of a joy that was not based on the poor conditions around me. I was content. And while I wouldn’t consider myself a performer, I was a creative: I drew mountains forever after I learned about Georgia O’Keefe; I wrote a poetry book in elementary school; I was PigPen in our Charlie Browne musical. But according to my mother, no matter where I was, I always “felt” for others. I still deeply feel for others, past and present. And this past week, while on a book tour, I shared a story of another brave girl, forced to be a warrior. Her name was Celia.

Celia. The Girl Warrior.

I learned about Celia when I first started teaching a course called “African Americans and the Law” at Lehman College. The instructor prior to me framed the entire course through the lens of criminal justice. When we think of incarceration, what comes to most people’s minds are Black and brown men and boys, the courtroom and prison. What does not easily come to mind are the many girls, women and non-binary folk who also are entangled in not just a legal system, but a culture that makes our journeys (intentionally) invisible. The ways our legal system impact particularly Black femme bodies requires just as much space, if not more in the spirit of equity. So there I was, a new teacher, digging and researching. Gathering books like Dorothy Roberts “Killing the Black Body,” and reading about the federal eugenics programs mandating the sterilization of Black youth, like the Relf sisters. And then I found Celia.

You should look up the case Celia, a slave v. The State of Missouri. What you should know is this: Celia was born at a time where Black people were, by law, property. She never had a girlhood because she was never a person in this society. When she was purchased at the age of 14 by a Robert Newsome, she was raped by him before she even got to the plantation. She bore two of his children. And one day, at the age of 19—pregnant now for the third time—after he announced that he was going to rape her again that evening…and after she pleaded with his two daughters to please prevent their father from raping her (they ignored her)…she hit him over the head with a wooden stick the night he came into her quarters. He died and she burned his body.

The tragedy of Celia—doubly disregarded due to race and gender—was not a new phenomenon; enslaved women had to perform labor non-stop—during the day, and at the pleasure of their owners at night (or whenever; time of day was not a factor). It is, indeed, the mass forced nonconsensual pregnancies and raping which created a population of people never envisioned to be loved as human. Survival was a mental, emotional and spiritual journey, one that psychology experts would share had to include some form of disassociation and a lot of coping. But there were some who rebelled. And the punishment for rebellion was immediate death—no questions asked.

So how the hell did Celia end up in a courtroom? With an attorney? How is it that a non-human, by law, could have a court case?

The short answer is a relative of the estate demanded a trial against Celia—a very interesting move. As a result, she was assigned an advocate (also interesting) and asserted self-defense. Celia’s brave act was during a time (1855) where a nation was still trying to understand the concept of “rights” for non-white males—including the rights of white women. But even though self-defense was a somewhat recognized defense for white women, the judge in this case instructed the jury that it could not apply to Celia because Robert gave her notice that he was coming in her room to have “intercourse” with her—and therefore it could not be rape. Celia was found guilty of first degree murder. She was executed by hanging. But not until she gave birth to her child (because that child was still valuable to them, and perhaps more valuable than Celia). Is it wrong for me to relish in the fact that the child was a stillborn? I don’t think so.

The judge in that case would three years later be appointed to the Supreme Court. Where he would practice his supremacy again. In the Dred Scott case.

But here’s what they could not bury: the record. This case may arguably be the earliest incident of the recognition of the humanity of a Black girl and woman. Only human beings are involved in cases. Only human beings can be charged with murder. In their quest to justify their lynching of her, they also validated that their wildest nightmares were true: Black people are humans. Full of emotion. Aware of their agency. And every now and again, their fight disrupts everything.

*********

Embracing the warrior in me.

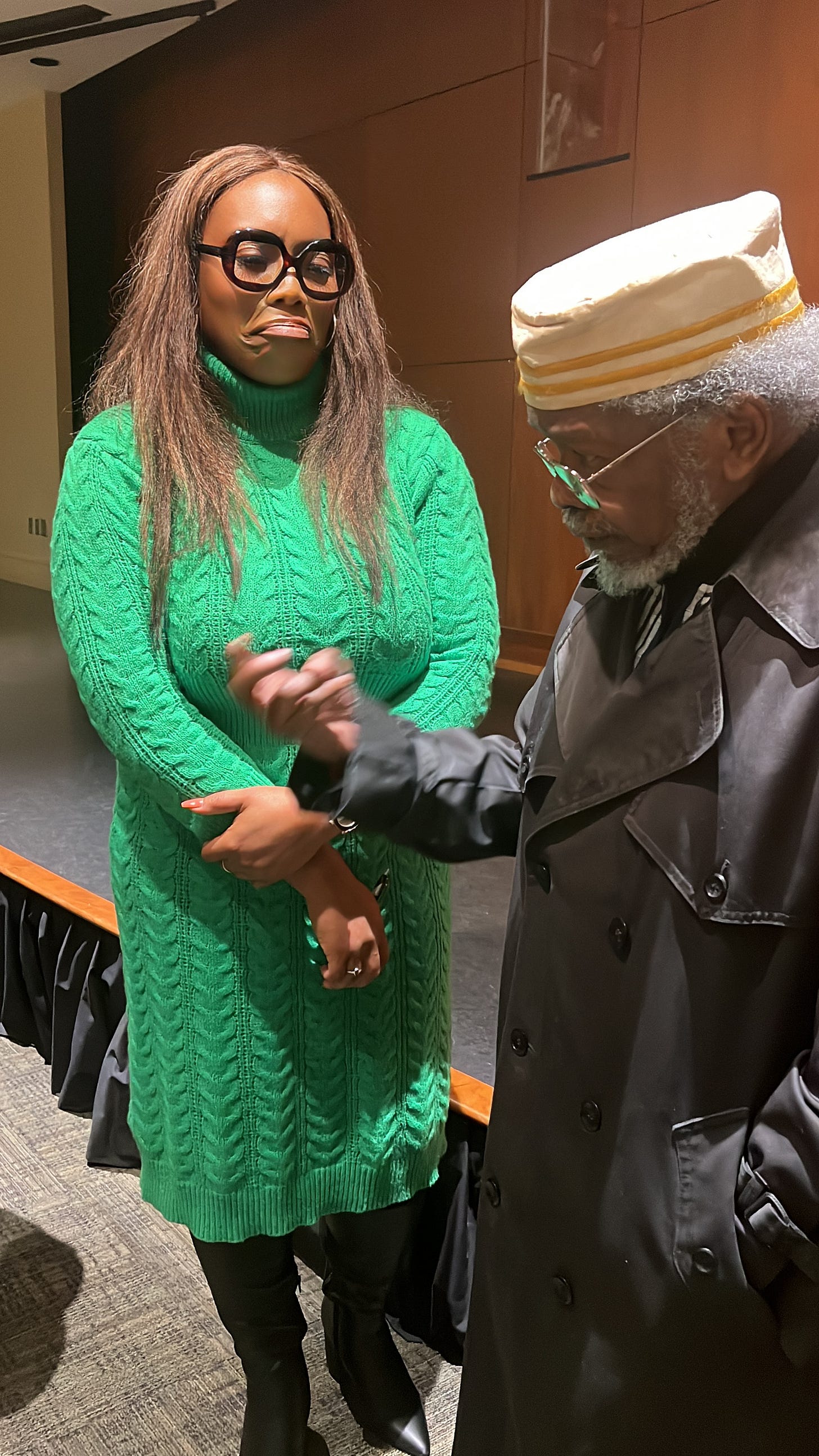

I was honored to be the 2023 Mahmoud El-Kati Distinguished Lecturer at Macalester College in Minnesota. I was doubly-honored when I was treated to a private dinner with Elder Mahmoud (and his son, who happens to be Stokely Williams, the lead singer to one of my favorite bands, Mint Condition). To be in the presence of a living Black intellectual, who knew personally the likes of James Baldwin, Ghana’s first president Kwame Nkrumah, and met renowned educator and philanthropist Mary McLeod Bethune when she was in 10th grade, was a life shifting experience, even while feeling like a normal family dinner. We sat in a small Twin Cities restaurant—him eating his bean chili, and me eating my chicken and wild rice soup. And he says to me mid-bite “I read about you. Do you know who you are?” I put my spoon down; where I’m from, when elders are trying to tell you something deep, you straighten your back to receive it. I waited until he was ready. “You are in the spirit of a particular kind of intellect. You are one with the people. You are kin to Ida B. Wells. An Anna Julia Cooper.” He rattled off a couple more names, but I was so emotional, I just sat there. I recalled a similar feeling when a sista stopped a business development meeting to say to me “You channel Florence Kennedy.” I froze. These are specific kind of leaders to me: bold, visible and masters of fact, clear that liberation must have narrators and truthtellers who are able to move people to action. I felt not only seen but also held by an ancestral tribe that impacts how I lawyer, how I consult, how I coach, and how I design. Admittedly, now just moments from my lecture, I was also nervous: I don’t want to let this professor emeritus genius down. I opted to not go to the reception and focus on my presentation, merging thoughts from my book “The Equity Mindset,” into a theme called: A Space for Celia. The goal: Could I engage this audience to design a world that would finally welcome the fullness of all she held, all she was denied, and all she had to fight for?

I stood at the podium and class began. After a standing ovation from a packed auditorium full of students, alum and community leaders, the final word belonged to Elder El-Kati.

“Professor Counsel,” he said, “I know who you are. You…you are a love warrior.” I was so still as he stood in front of everyone but his eyes were locked on me. “Unnhmm, that’s what you are. Y’all need to be careful. This one, she truly respects people. She actually loves all people. That is her strength. You are a godsend. A love warrior is an undercurrent, you are connected to a long line of love warriors. And we thank you.”

He said more. Much more. And I have it on video, even though my hands were shaky. I never, ever thought there would be a moment where the word “warrior” wouldn’t feel exhausting, or painful, or extractive. And without going into the full why, the word “love”—and feeling everything humanity is going through—can make one feel weak at times, in ways hard to describe. I rejected being called a warrior before. But in this moment, it was right. I think the difference for me is that the engine behind my fight was as authentic as the fight itself; that there are some people who want to be known for their strength, but I want to be measured by how well and ferocious I respond to the needs of people—and how well I can help others do the same. And for me, that includes loving those who came before us, like Celia., and connecting it to the many fights we have today.

I met an amazing intellect. He called me a Love Warrior. And I believe that’s who I am.

Reflection prompt: What spirit/energy/essence drives you as you move through journeys? What do you know are the consistent traits about you that you couldn’t hide even if you wanted to? Who else embodies similar energy—past, present?

for Celia.

Ifeoma Ike is the author of the new book and #1 new release “The Equity Mindset,” found wherever books are sold, including at New Orleans bookstore, Baldwin & Co.

Whew, what a word! When the elders speak, we listen and we carry their baton onward!